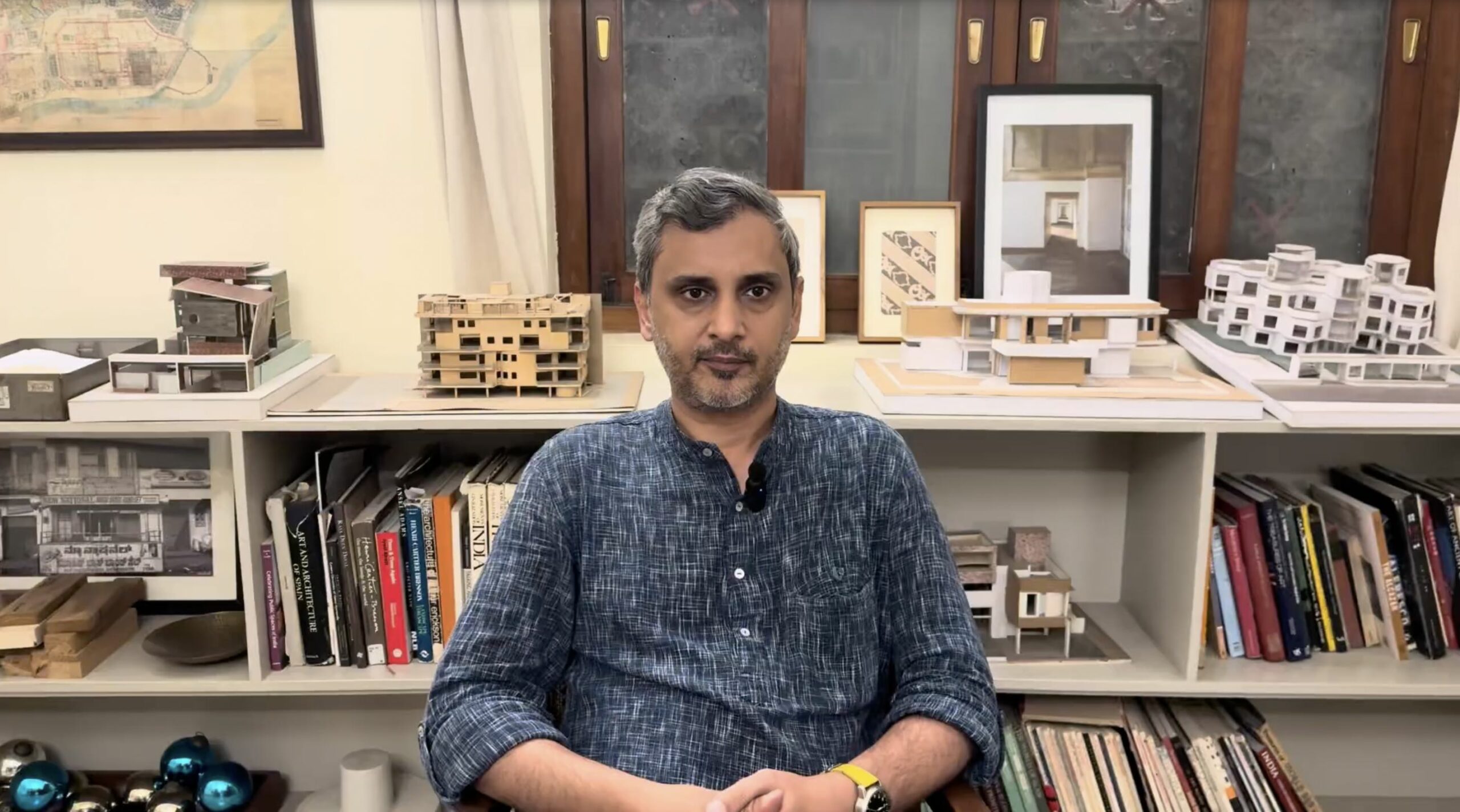

An architect committed to designing environmentally friendly homes, Parikshit Dalal takes a nuanced view of floating cities. While the idea may seem futuristic, he believes it deserves careful consideration, given the technological possibilities, cultural adaptations and ecological imperatives involved.

Living on water: an ancient idea, a renewed challenge

‘Seventy per cent of our planet is covered by oceans,’ he points out, emphasising that humanity has always exploited the sea for travel, fishing and resources, but rarely for permanent habitation. Historically, ships have sometimes served as temporary homes, such as during the long voyages between Europe and India.

Today, rising sea levels and global warming are prompting us to consider new forms of housing. « Even on land, lifestyles have changed. The small houses of yesteryear have given way to increasingly taller structures. Why shouldn’t architecture on the ocean evolve as well? »

Between necessity and choice

For the architect, life on the water will probably not become the universal norm, but it could be a solution for specific situations. Some coastal or riverside areas threatened by rising water levels could opt for hybrid solutions, ‘living partly on land and partly on water,’ as a step towards adaptation.

He also sees floating cities as a laboratory for other human adventures: ‘Living on water is one step closer to living in space,’ where we have to live in compact modules in an environment that is unnatural for human beings. The technologies developed for one could inspire the other.

A lever for ecological awareness

According to him, living in direct contact with water would encourage a change in the way we view the ocean. Today, it is often seen as an invisible dumping ground, receiving effluents and plastics that eventually re-enter the food chain. ‘The closer we live to water, the more we develop a relationship that encourages us to take care of it,’ he says, comparing this evolution to the way society has learned to protect its forests.

Small structures or megaprojects?

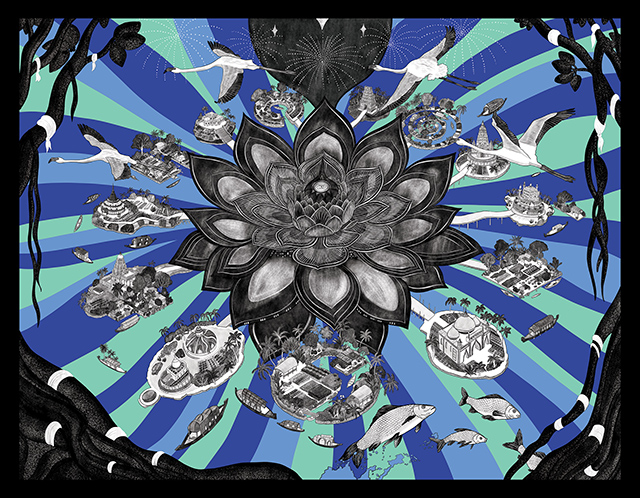

Parikshit Dalal distinguishes between several approaches. The traditional floating villages of Southeast Asia—in Cambodia and Laos—where people live on the water with schools, shops and places of worship, show that a sustainable way of life is possible on a small scale. In contrast, massive land reclamation projects such as those in Dubai or the historic expansion of Mumbai pose serious environmental problems: destruction of mangroves, disruption of ecosystems and poor drainage.

He advocates modest, environmentally friendly structures that incorporate modern water treatment and energy production technologies.

Rethinking the ecological debate

For the architect, the argument that living on water is inherently more harmful than living on land does not hold water. ‘We cause as much, if not more, damage by living conventionally on land,’ he says, citing urban soil sealing, vegetation loss and worsening flooding. The real issue is not the medium – sea or land – but ‘sensitivity and the correct use of technology’.

A testing ground to be explored

He refuses to pit the two models against each other and urges us not to prematurely rule out an option that could ultimately improve our way of life. « Human civilisations have always thrived on imagination. We will make mistakes, but we have to try. ‘ The lessons learned from the destruction of terrestrial environments could inspire sustainable solutions for floating habitats.

A laboratory for ideas and adaptations

For Parikshit Dalal, floating cities are above all a field of experimentation. He believes that many technologies, concepts and lifestyles will evolve as trials progress. ’ If people don’t try, we’ll never know if it’s really good or bad. The lessons learned from land urbanisation — including its mistakes — could guide the design of more harmonious aquatic habitats, reducing risks and accelerating the search for optimal solutions.

A concept under exploration

In his view, it is too early to decide: ‘We’re still in the testing phase.’ He refuses to label the idea of living on water as good or bad. The potential, like the challenges, still needs to be explored. The important thing is to keep an open mind: « All exploration should be encouraged, because it is human imagination and the willingness to go beyond what has already been done that drive us forward. «

Costs, transition and coastal settlement

He acknowledges that adopting this way of life would require significant initial investment and technical adaptation. However, he anticipates gradual development, starting with coastal areas that are familiar with life by the water. The history of civilisations proves it: ‘All our great civilisations developed along major rivers or lakes.’

The technologies already exist to create floating or amphibious structures capable of adapting to changes in water levels, but they will have to contend with complex factors such as tides, seasons, climate, monsoons and the as yet poorly understood effects of climate change.

Between universal appeal and real necessity

For the architect, the aesthetic and sensory appeal of aquatic environments is undeniable: sunrises over the water, a feeling of openness, direct contact with the element. But he also questions the motivation: « Do we want to live on the water out of necessity or because it’s an appealing idea? ‘

He draws a parallel between this question and the appeal of space, a place devoid of water, land and trees, yet which nevertheless inspires a desire to explore. For him, this is not a debate to be settled, but ’a work in progress » where reflection feeds technology and vice versa.

Universal questions of equity and governance

Whether on land, in the ocean or in space, the same issues arise: equitable access to resources, protection of ecosystems and the rights of populations. ‘We have abused the earth as much as we are beginning to abuse water.’ All human settlements must therefore be accompanied by rules that guarantee sustainability and social justice, so that everyone can benefit from nature without compromising its cycles.

Towards a hybrid model

He imagines a future where land and water complement each other: hydroponic farming on marine platforms to compensate for soil depletion or regeneration, aquatic structures dedicated to energy production or leisure, and alternating use of land and water spaces. This gradual transition would allow populations to get used to this way of life, while refining technologies and governance models.

For him, success hinges on one key idea: ‘The broader concepts of sustainability and equity must be addressed before we get into the technical details.’

Testimonies from the same panel