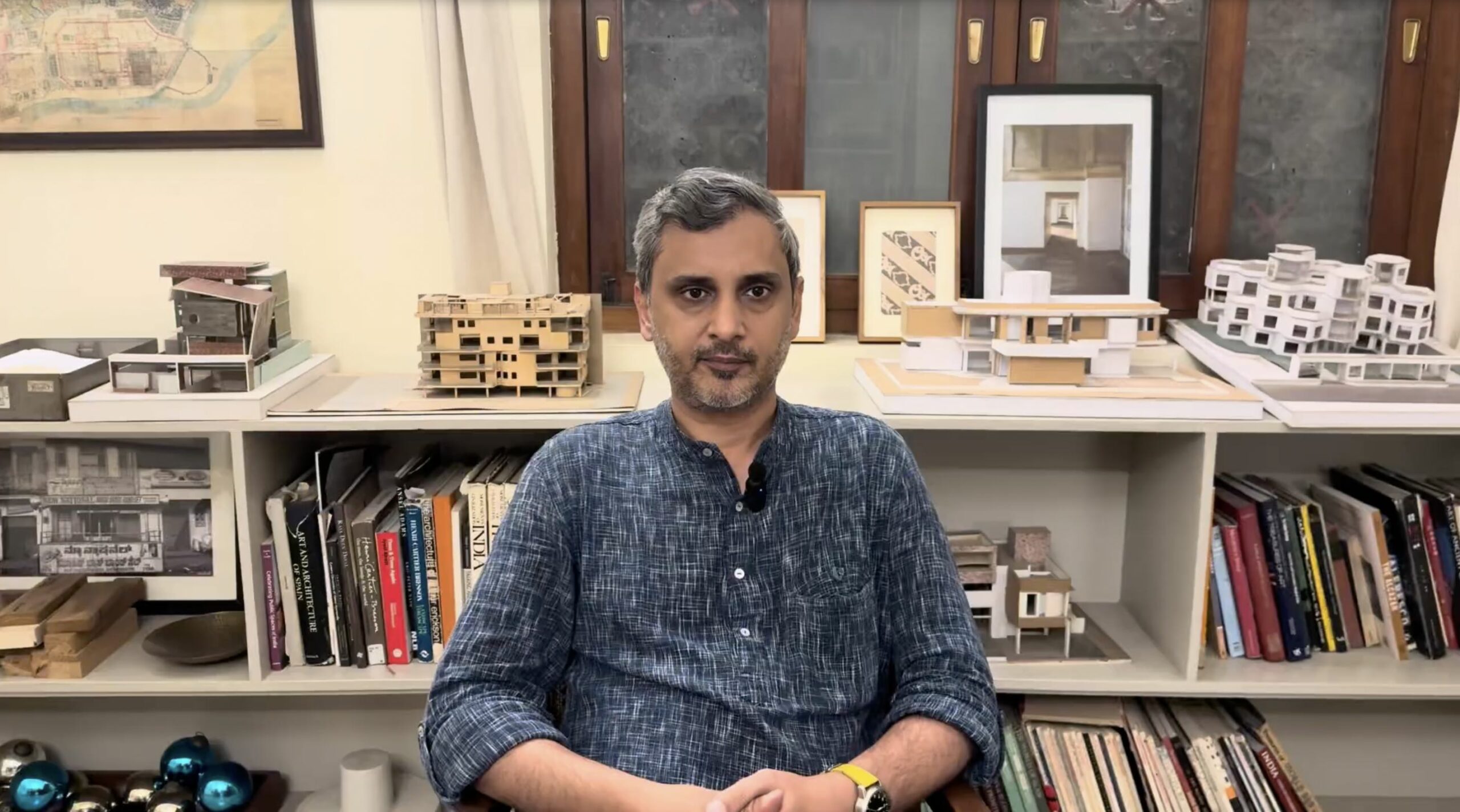

Pariskshit Dalal is an architect. In this interview, he shares his analysis of current urbanisation trends and outlines concrete ways to rethink how we inhabit the planet.

Towards a reinvention of architecture and the city

Pariskshit points out that the human population has more than doubled in a century, from around two billion at the beginning of the 20th century to nearly seven billion today. This rapid, unexpected and poorly anticipated growth has led to massive urbanisation, particularly in Asia, Africa, India and China. ‘No one realised that we would need to house so many people in cities,’ he points out, denouncing ‘chaotic’ urban areas that have seen a decline in quality of life, air and water.

The legacy of old models and the dead end of the suburbs

According to him, the collective imagination remains marked by the ancestral model of a detached house on a plot of land. This dream, transposed to an urban environment, gave rise to suburbs: small plots, terraced houses, lack of light and ventilation. The arrival of the car in the 20th century exacerbated the situation: » Cars invaded all the space that was intended for people to move around,‘ making streets hostile and causing open spaces to disappear.

The limits of the current vertical model

Verticality, initially designed to free up floor space, has been misused: ’We took these towers and placed them next to each other, as in the suburbs. ‘ Residents now live in a ’vertical suburb‘, where extreme density and a lack of greenery persist. However, a new demand is emerging: open spaces, terraces, gardens, unobstructed views, and distance from pollution and noise. ’We will never be happy if we don’t live close to nature, » he asserts.

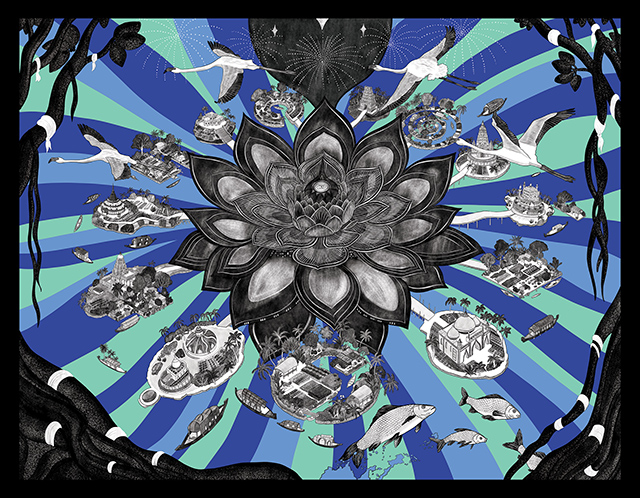

Reintroducing nature and rethinking density

He proposes creating smaller but denser urban ‘clusters’, freeing up land to provide views, sunshine, air and biodiversity. These clusters would be linked by fast and efficient transport, reducing commuting distances. The aim is to limit urban sprawl, bring green spaces closer to homes and avoid exhausting daily commutes: ‘We can’t spend three to four hours of our daily lives on transport.’

The materials of tomorrow

The debate also focuses on construction, which is responsible for a third of global carbon emissions. Concrete and steel are among the most polluting materials. He advocates the use of bamboo wood, obtained from compressed stem fibres: « A 20-storey building made of steel and cement is equivalent to 1,000 cars emitting carbon dioxide in a year. The same building made of bamboo emits 75% less carbon. This material, which comes from a grass that grows back in three or four years, significantly reduces the carbon footprint, even if cement and steel cannot be completely eliminated in the short term.

The role of culture and collective will

He believes that the economy has long dominated urban planning, relegating the aspirations of residents to the background. But he believes that ‘culture will fight back’ and that citizens ‘will find a way to dominate technology, politics and the economy’ to impose a more sustainable way of life. The transition will have to combine technical innovations, cultural change and courageous political choices.

Hopes and challenges

He believes that the world’s population will peak at nine billion before declining, which could facilitate the implementation of environmentally friendly solutions. But climate change, which is already tangible, requires swift action. The oil, traditional energy and construction lobbies will remain powerful, but ‘their time will also come’. He calls for better resource management and a drastic reduction in waste: ‘In India, 40% of the food we grow is wasted. It’s criminal.’

The future of cities and architecture, he concludes, depends on aligning what we really want with the efforts we make: ‘People’s energy and attention will have to focus on our way of life.’

Taking inspiration from nature to rethink our lifestyles

For Pariskshit Dalal, observing nature offers essential lessons in efficiency and harmony. « Look at bees: they live in very dense swarms, in complex hexagonal structures. They have found a way to live in a very compact and efficient way. This economy of materials and ability to create solid structures with fine elements should inspire architecture and urban planning.

He advocates a return to natural materials and forms and geometries inspired by living organisms, not only for building, but also for organising more efficient communities. Education plays a key role here: ‘When young children are exposed to nature and taught how it works, it’s the best way to shape their minds.’

Cooperation and sharing: the example of agriculture

The connection with nature goes beyond just greenery. It implies a collective, supportive and rational way of life in terms of resource use. The architect deplores the inefficient fragmentation of agricultural land in India, a legacy of family divisions: « It is very inefficient to farm when you have very small plots of land. He proposes the creation of agricultural cooperatives that pool production resources to increase efficiency, productivity and prosperity, thus transposing his vision of compact, integrated urban units to the agricultural sector.

Restoring the primacy of nature

He insists on the need to put nature back at the top of the agenda, ahead of technology: ‘Today, it’s technology, us and nature. We need to reverse that order.’ He cites an initiative in Delhi where children follow the path of water from the tap to the mountains to gain a practical understanding of natural cycles and the resource production chain. Such approaches, he believes, instil lasting respect and prevent resources from being taken for granted.

Reconciling economics and ecology

The cost argument, often used to dismiss eco-friendly materials, needs to be put into perspective. What seems more expensive in the short term may prove to be more economical in the long run. Public policy, financial incentives and the rise of large-scale production can reverse the trend. « If demand increases, there will be 500 factories. Prices will fall and the product will become cheaper than steel and cement, » he says of bamboo wood.

He points out that the same players who opposed renewable energies are now investing in wind and solar power. This shift, driven by economic and ecological survival, will eventually take hold in all sectors.

A possible future

Despite the scale of the challenges, Pariskshit Dalal remains confident: ‘The question is simple: do you want to live and do you want your children to live, or do you want the Earth to collapse?’ For him, the answer is clear, and it is this obvious fact that will push societies, industries and governments to find solutions, even if they are difficult and painful.

Testimonies from the same panel