Susmita has spent half of her nearly thirty year professional space career in human space exploration – designing space habitats, rovers, spacesuits and space mission simulators. She began her professional career working with NASA and Boeing before turning entrepreneur. Between 2001-2021, she co-founded and ran three small space companies one of which – LIQUIFER Systems Group (https://liquifer.com/) specialises in the design of space habitation, exploration and transportation systems.

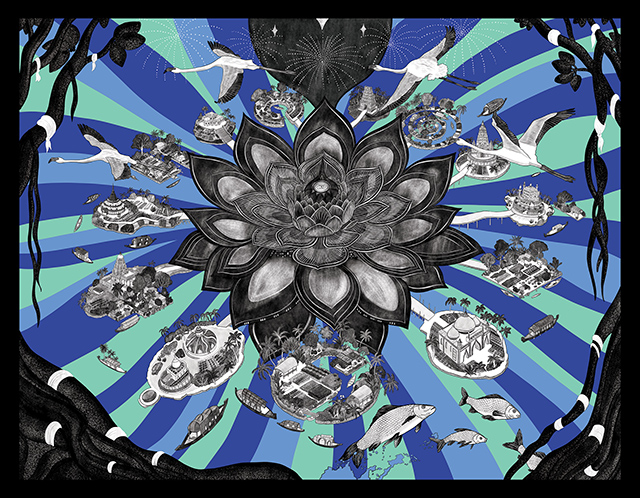

A visionary, she also co-founded the City As A Spaceship (CAAS) Collective (http://www.cityasaspaceship.org/) that looks at reciprocities in architecture and design for living and working in extreme environments, on an off the planet. Often technologies developed for space can used here on Earth, including in aquatic or coastal environments threatened by climate change.

Susmita’s design thinking combines innovation, ecology and reflections on progress. She advocates integrating knowledge systems from indigenous communities to treat our home planet (and other planetary destinations we choose to visit) with care and steer away from ‘extractive’ and ‘exploitative’ approaches used by colonial and capitalist systems.

*Living in the sea: a necessary challenge*

Susmita Mohanty reminds us that ‘the planet we call home is two-thirds water’ and that we have not yet explored the possibility of living on and under water for long periods of time, establishing ‘families, communities, villages and even micro-cities’. While a few architects and designers have ventured into this field, it is still ‘highly experimental and conceptual’.

For Susmita, ‘it is entirely possible, from a technological point of view, to create thriving communities who live on water.’ The Earth is home to nearly 8 billion people. It cannot sustain large masses of people, especially ones with consumeristic lifestyles in the world’s cities. Consumerism, combined with increased frequency of climate spikes and rising sea levels caused by global warming make ‘living on water’ a compelling option. Her native state of Orissa on the east coast of India is already experiencing human displacement from coastal towns. According to some estimates, nearly five kilometres of coastal land is washed away by the rising ocean each year’. In her view, large coastal cities such as Mumbai, San Francisco and Hong Kong will ‘either have to be relocated eventually or else be swallowed by rising waters’.

*Turning urgency into opportunity*

Countries like Australia and the United States, and potentially others involved in offshore processing or holding facilities, have built detention centers on water or on islands located in the sea. Australia uses offshore processing for asylum seekers in other countries like Nauru and Papua New Guinea. The United States operates Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba, located on a naval base in the bay.

Susmita sees this as ‘a very negative view’ of how water can be leveraged in terms of habitation and advocates for ‘a positive approach’ that is inclusive and offers sustainable solutions. She cites the example of the ephemeral islands in the Brahmaputra river in Assam, eastern India. « Chars » (or « Chapori ») are riverine islands and landmasses formed by silt deposits in the lower parts of the Brahmaputra River’s basin. These islands are constantly shifting due to a unique pattern of erosion and deposition, leading to their migration downstream, making them inherently unstable and flood-prone. Certain nomadic communities live on these ‘chars’ in bamboo huts, cultivate rice and move to a new char when the last one dissolves. This way of life demonstrates, in her view, that ‘there is always a way […] to make things ecological if we want to.’

*From space engineering to aquatic architecture*

Susmita’s design experience could be applied in part to marine habitats. For space habitation, she and her colleagues designed ‘climate controlled, pressurized, hermetically sealed modules where a crew […] can live comfortably in a shirtsleeve environment,’ incorporating closed-loop life support systems. She points out that lunar space infrastructure is often tested underwater, as this environment allows for the simulation of reduced gravity conditions. According to her, this ‘reciprocal design logic’ could inform the creation of habitats on or under water, here on Earth, while also preparing for future settlements on other celestial bodies.

*Towards planetary reciprocity*

For the architect, this reciprocity also applies on a solar system scale. She cites Europa — the smallest of the four Galilean moons of Jupiter. Europa is an icy moon of Jupiter that is a key target in the search for extraterrestrial life due to evidence of a vast, salty ocean of liquid water beneath its icy surface, potentially containing more water than Earth’s oceans. Europa could be a potential future aquatic environment that Earthlings might choose to explore. Technologies developed for underwater habitats and transporters on Earth could find direct application there.

‘Reciprocity is inherent in everything we do,’ she says, convinced that the future of architecture will involve constant dialogue between terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments.

*Closed systems for Earth and space*

We can draw inspiration from closed loop life support systems we design for habitable spaceships and apply these principles to life on Earth, just as the solutions developed for our planet can inform how we will one day live in other planetary destinations.

For example, in Bangalore, every new residential campus is legally required to recycle all greywater and blackwater on site. It has similarities with the closed loop systems being employed for humans living in low earth orbit: there is little or no waste, everything is recycled and reused.

While 100% recyclability remains out of reach, it is nevertheless possible to achieve a rate of 80 to 90% when there is a will to do so. It is precisely this experience, and the lessons it offers, that could guide the development of autonomous and sustainable systems, which will be essential in the future for establishing settlements on other planets.

*Redefining progress*

For Susmita Mohanty, ‘progress is a relative term’ that varies according to each person’s perception. Her vision is not limited to industrial progress, but includes ‘access to medical infrastructure,’ and above all ‘a very important component of progress, which is mental infrastructure.’ She believes that the industrial world’s approach over the last couple of centuries is insufficient and driven by a desire for infinite growth. That is flawed because it leads to extreme consumption, waste and ecological degradation. Progress should not be reduced to ‘building more, faster and making things cheaper’: it requires, in her view, greater foresight and a dimension of inclusion of all species that we share our home planet with.

Noting that ‘we have had too many wars’ and that ‘we waste billions of dollars building war machines,’ she calls for investing these resources in research into sustainable solutions: ‘How can we transition out of using fossil fuels? How can we build satellites and rockets that don’t pollute? How can we communicate with other sentient beings here on Earth? How can we improve our quality of life by connecting with and revering nature (as indigenous peoples do) instead of constantly wanting to monetise it (as colonial and capitalist systems do)?.’

*Indigenous knowledge as a compass*

She then turns to indigenous communities, which are present in every country. These societies, which harvest and cultivate on a small scale, show that it is possible to meet one’s needs while promoting carbon sequestration. ‘They take only what they need,’ she reminds us, highlighting the contrast with modern agriculture, which contributes to the current carbon imbalance.

For her, traditional knowledge ‘must be studied or researched’ in order to redefine the very notion of progress. ‘I think they are more advanced than us in many ways,’ she says, not only in their ecological practices, but also in their social structures. She therefore advocates bringing ‘urban life and indigenous life’ closer together, finding a balance between these two models. This balance, she concludes, ‘would mean progress, as I understand it.’

Testimonies from the same panel