Kadambri Komandur, designer, and Namrata Narendra, architect by training working on urban issues related to water, are leading an original project in Bangalore dedicated to the Vrishabhavathi River. Both have a keen interest in maps, landscapes and the relationship between communities and their aquatic environment. Their goal is clear: to revive memory and attention around a waterway that many ignore or consider lost.

Awareness born out of lockdown

The project was born during the COVID-19 pandemic. The two designers noticed a surprising phenomenon: ‘When COVID arrived […] the water became very clean.’ The temporary closure of industries was enough to restore the river’s forgotten clarity, demonstrating that ‘it wasn’t an unsolvable problem.’ For them, the lesson is clear: this is not inevitable, but rather a question of priorities.

Revealing the diversity of connections to the river

Like any urban river, the Vrishabhavathi faces a multitude of challenges: industry, institutions, agriculture, fishing, domestic use and education. Some communities, such as the Dhobi Ghat laundry workers, depend directly on its water. Downstream, farmers paradoxically exploit the pollution: ‘they have almost come to depend on pollution to grow their crops.’

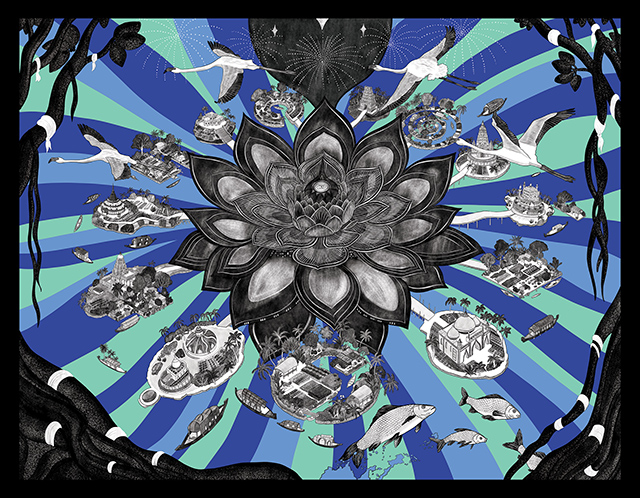

Biodiversity is also at stake: the example of the machete fish, an endemic species now threatened by development, illustrates the fragility of the balance. Kadambri and Namrita insist on the need to ‘make people understand […] that the river has a soul’ and that it has a vital relationship with the city.

Art as a vehicle for connection

To reach the public, they have chosen the graphic novel format, which they believe is better suited to creating an emotional connection than a simple technical report: ‘Data doesn’t really reach the general public […] it’s usually memories, stories and poetry that touch people.’ ‘

They are particularly interested in the perspective of children, which is often ignored: ’What does a child see in a river? How does it depend on it?‘ Drawing then becomes a tool for participation, memory and appropriation: ’If we could instil a sense of belonging from an early age […] it would be wonderful. ‘

Capturing the complexity of local realities<

The two designers reject a top-down approach where urban illustrators impose their vision. They favour work rooted in local perceptions, such as at Dhobi Ghat, where a rare model of collective ownership persists, promoting ’social cohesion » and shared resource management.

This model contrasts with the growing individualisation of water use in cities.

A project that does not claim to solve everything

Kadambari and Namrata are aware of the limitations of their approach: « It may not solve any problems […] but it can help people become aware. ‘ The most important thing for them is to raise questions: ’Books have the power to make people ask questions, and there is immense power in asking the right questions. »

They are convinced that change will not come from a single work, but from the ability to multiply these spaces for dialogue and memory around the river.

Testimonies from the same panel